The Eighteenth Century: America

The eighteenth century, in America, was a period of significant development. It shaped the direction of the United States in a different trajectory from Europe, and that influence continues to the present.

This is part of a series on the eighteenth century. You can also see the Tides of History, the Great Events, and Great Britain.

The Glorious Revolution in Great Britain led to changes for the colonial governments, especially the downfall of the Dominion of New England. The Dominion was a centralized form of government imposed by Charles II and James II. When James was deposed, the colonial governments reverted back to their original government charters.

The colonial period of British America was marked by constant wars and conflicts; many of them were the result of British and French conflict in Europe that spilled over into America. Often, this warfare was most intense in the loosely-defined interior borders, where both powers sought alliances and friendships with Native Americans. The French, in particular, relied on native allies, since the holdings of New France (generally the region of modern-day Canada) were far less populous than the British holdings.

The colonial period of British America was marked by constant wars and conflicts; many of them were the result of British and French conflict in Europe that spilled over into America. Often, this warfare was most intense in the loosely-defined interior borders, where both powers sought alliances and friendships with Native Americans. The French, in particular, relied on native allies, since the holdings of New France (generally the region of modern-day Canada) were far less populous than the British holdings.

The fighting often involved guerilla-type warfare, surprise attacks, and raids on remote colonial settlements. King William’s War (1688-1697), for example, was fought mostly in New England and Canada against the French; it was a spillover from the European Nine Year’s War.

The Salem Witch Trials (1692-1693) were infamous for the deaths of around 25 people. The Puritan establishment prosecuted individuals accused of witchcraft, using dubious evidence and leading to the deaths of many innocent persons. Two prominent puritan theological leaders were involved: Increase Mather warned against the use of spectral evidence, while his son Cotton Mather defended the trials. During this time, the colonies of Massachusetts and Connecticut, in particular, remained firmly under Puritan control.

Virginia was the colony of the genteel, identified with the official Anglican church, and more closely aligned with the aristocracy of Britain. It was the wealthiest British colony in the New World, governed from Williamsburg; the College of William and Mary (1693) was founded in Williamsburg and educated, among others, Thomas Jefferson.

In Connecticut, the ‘Collegiate School’ was founded in 1701 to train congregational ministers. This was in response to the liberalizing of Harvard; when Elihu Yale gave a significant gift from his fortunes in the East India Company, the school was renamed in his honor.

Queen Anne’s War (1702-1713) involved the colonies in the European spillover of the War of the Spanish Succession, while Dummer’s War (1722-1725) was a separate conflict between New England the Wabenaki Confederacy. Each war led to conflict on the frontier borders.

During this time, the colonies continued to change forms. In 1702, East and West Jersey were combined into the single colony of New Jersey. The Province of Carolina was divided in 1712 into a north and south section – an official recognition of what had been the de facto condition for some time. In 1732, the colony of Georgia was formed through the work of James Oglethorp (1696-1785). Oglethorp was a Minister of Parliament who became concerned about rampant abuses in debtor’s prisons; as a philanthropist, he aimed to create a colony for some of the imprisoned to find sanctuary in the New World. Georgia was originally established without slavery, but this eventually changed, and the colony became a crown colony in 1752.

While Georgia started out without slaves, all of the colonies were involved in slavery, though the vast majority of slaves were held in the southern colonies. By 1770, the colony of Virginia held 187,000, far more than any other colony. Georgia and South Carolina, by that time, contained over 60% of their populations as slaves. The southern colonies developed labor intensive plantation systems that cultivated tobacco and rice, while the economies of the northern states relied less on this type of production. Whites routinely worried about the possibilities of slave results; the Stono Rebellion (1739) in South Carolina was the most significant revolt of the century and led to the deaths of around 70 people. Many of the northern states would abolish slavery by the end of the century.

The colonies were radically shaken by the Great Awakening, a conglomeration of religious revivals that climaxed around 1739-1742. Religious interest rose throughout the colonies, to the point that some visitors described it as the only topic of conversation on city streets for months at a time. While these years were the climax, sporadic revivals occurred before and after. Churches increased rapidly, sometimes doubling their numbers in a matter of months as unbelievers flocked to hear preaching by men like George Whitefield, the English evangelist. The Awakening emphasized the necessity of personal conversion and the grace of God in salvation, but they were sometimes marked by uncommon physical manifestations such as fainting and screaming. Churches were generally divided into two camps: the ‘old lights’ opposed the awakenings, while the ‘new lights’ accepted them. Eventually the new lights divided into moderate and radical groups, with the radicals in favor of the physical manifestations, and the moderates more cautious. The Awakening laid a deep religious foundation for America, and it lies at the roots of modern evangelicalism.

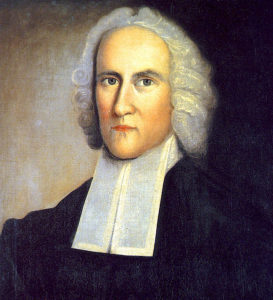

The most famous American theologian in the Awakening was Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758), a Northampton, Massachusetts pastor who experienced revivals in his own church. He delivered the sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” at Enfield, Connecticut in 1741, and it remains one of the most famous sermons in American history. Edwards was a friend of graduate of Yale and a friend of George Whitefield. He was called to the presidency of the College of New Jersey, but died the same year.

The most famous American theologian in the Awakening was Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758), a Northampton, Massachusetts pastor who experienced revivals in his own church. He delivered the sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” at Enfield, Connecticut in 1741, and it remains one of the most famous sermons in American history. Edwards was a friend of graduate of Yale and a friend of George Whitefield. He was called to the presidency of the College of New Jersey, but died the same year.

Yale opposed the Awakening, so the College of New Jersey was formed by the New Lights; later the name was changed to Princeton. It was founded to train ministers, but the Founding Father John Witherspoon, a president of the school, shifted the focus from ministerial education by the end of the century.

Another friend of George Whitefield was Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), a man who listened to Awakening sermons but never converted to the faith of his evangelist-friend. Throughout his varied career, Franklin was a Philadelphia publisher, an inventor, and later an ambassador to France for the fledgling nation.

The War of Jenkin’s Ear (1739-1748) was a conflict between the British and Spanish that primarily occurred in the Caribbean, but involved colonist troops. The war was technically triggered by an event that happened years earlier (1731), when Spanish troops boarded a British ship and the captain, Jenkin, lost his ear in the scuffle. The war merged into the larger War of the Austrian Succession, which manifested as King George’s War (1744-1748) in America. At the Siege of Louisbourg, British and colonial troops captured a French fortress in Nova Scotia. The French had previously spent 25 years fortifying the site; it was returned to the French during treaty negotiations at the end of the war.

More conflict with the Nova Scotians (‘Acadians’) arose during Father Le Loutre’s War (1749-1755), when New Englanders battled the Acadians and their native allies. But the truly great conflict of colonial America was the French and Indian War (1754-1763). It began with the tiny Battle of Jumonville Glen, when a young George Washington ambushed a minuscule force of French Canadians; his victory was quickly reversed when he was forced to surrender his Fort Necessity. The British sent a well-equipped expedition against the French in the Braddock Expedition, but they were miserably defeated by a surprise attack; Braddock learned too late that the wars on the frontier were fought Indian-style, not with large columns of regular troops.

More conflict with the Nova Scotians (‘Acadians’) arose during Father Le Loutre’s War (1749-1755), when New Englanders battled the Acadians and their native allies. But the truly great conflict of colonial America was the French and Indian War (1754-1763). It began with the tiny Battle of Jumonville Glen, when a young George Washington ambushed a minuscule force of French Canadians; his victory was quickly reversed when he was forced to surrender his Fort Necessity. The British sent a well-equipped expedition against the French in the Braddock Expedition, but they were miserably defeated by a surprise attack; Braddock learned too late that the wars on the frontier were fought Indian-style, not with large columns of regular troops.

The Battle of Carillon (July 8, 1758) marked another important event in the war, and possibly the bloodiest day in America to that point. The French Fort Carillon was unsuccessfully assaulted by British soldiers, with around 3000 total casualties; the next year the British captured the fort and renamed it Fort Ticonderoga.

Eventually the war flared into the worldwide Seven Year’s War. It resulted in an unknown number of casualties in America, maybe around 15,000-20,000. The British victory led to the surrender of French Canada and its occupation by the British and the expulsion of the Acadians, many of whom later ended up in Louisiana under the name ‘Cajun.’

While native allies were involved on both sides of the previous war, Pontiac’s Rebellion (1763-1766) saw a major revolt by native Americans against the British; the rebellion was quelled, but it led to changes in how the British government handled the frontier areas of the colonies. This improved relationships with the natives, but it worsened relationships with the colonies, especially since it restricted immigration to the west.

By this point, the colonies had grown significantly. The population of the colonies doubled every 25 years, resulting in 2.4 million colonists by 1775 – about ten times the population of 1700. The colonies also contributed significantly to the economic power of the Empire. This growing influence came to the fore as the colonies felt mistreated; the spiraling costs of the Seven Year’s War had to be paid, but the colonists were not represented in the Parliament that volunteered their money. They were also frustrated by policies against immigration and what was viewed as a lax policy toward Roman Catholics in the newly-held lands of Canada. Added to this was the sense of being second-class citizens in the Empire, for colonial soldiers, fighting in the French and Indian War, were often put under the control of English officers without experience in frontier warfare.

The First Continental Congress, which convened in 1774 in Philadelphia, sought to address these concerns, especially the closing of Boston harbor following the Boston Tea Party the year before. The Congress chose an economic boycott and a petition to the king. When this failed to have its intended effect, the Second Continental Congress convened in 1775. It continued to meet until 1781, and it released the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. The Congress would function as the American government, and it drew up the Articles of Confederation.

The American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), as mentioned previously, started out with American defeats until the tide changed and France sent aid to the colonies. The Articles of Confederation (ratified March 1, 1781) created a limited central government, in which each state was treated as an independent country involved in a loose union for common defense. Yet the Articles were largely ineffective, since the government could not require troops, supplies, or money from the states, and the requests often went unanswered. Because the government could not force delegates to attend, it was difficult to ratify treaties.

The American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), as mentioned previously, started out with American defeats until the tide changed and France sent aid to the colonies. The Articles of Confederation (ratified March 1, 1781) created a limited central government, in which each state was treated as an independent country involved in a loose union for common defense. Yet the Articles were largely ineffective, since the government could not require troops, supplies, or money from the states, and the requests often went unanswered. Because the government could not force delegates to attend, it was difficult to ratify treaties.

As the states began to recognize the insufficiency of the Articles, public debate raged over the best solution. The Federalist Papers, published between 1787-1788, were written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay to argue for the Constitution and a federalist-style government. Eventually, the Constitution was ratified on June 21, 1788. It was a radical document for a time when European states remained absolutist in their approach. The Constitution provided for balancing branches of government to prevent despotism, and George Washington (1732-1799) was the first of the presidents. He was a Virginia plantation owner, the ‘father of his country,’ and perhaps the most influential American of the century, especially in light of his significant involvement in both the French and Indian, and the Revolutionary, Wars.

American politics quickly developed two camps, the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. The Federalists were led by Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804), who was the Secretary of the Treasury under Washington. Hamilton favored a larger government, national bank, and national debt. He was sympathetic to England and admired to the English form of government; the Federalists in general were more aristocratic in their approach, were anti-French, and found strong support in New England. John Adams, the second president, was their only candidate to win the presidency.

The Democratic-Republicans were led by Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) and James Madison (1751-1836). Jefferson was also a Virginia planter and the author of the Declaration of Independence. The Democratic-Republicans were small-government, anti-British, and pro-French, even in the face of the radical French Revolution.

George Washington was technically a non-partisan president, but he increasingly leaned toward the federalist position. Succeeded by John Adams, a former lawyer, the country entered the Quasi-War (1798-1800) during which French and American ships fought during undeclared war. America failed to repay debts to the French after the French Revolution, claiming that the debts were owed to the overthrown regime. The conflict was resolved in 1800, and Thomas Jefferson became president from 1801-1809.

Under Jefferson, America purchased the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803, providing money to the cash-strapped Napoleon. Jefferson opposed big government and privately admitted that he had no authority to authorize the purchase, but felt that it was a deal too good to pass up. He also presided during the Barbary Wars (1801-1805), two conflicts with the city-states of Tunis, Algiers, and Tripoli in North Africa. These governments were nominally part of the Ottoman Empire but practiced piracy if not given sufficient tribute; around 1000 died when Jefferson refused to pay the tribute and sent the American Navy to open the waterways.

The final American conflict during the ‘long’ eighteenth century was the War of 1812 (1812-1815), sometimes viewed as part of the Napoleonic Wars. The British impressed American sailors into the Royal Navy and continued to support anti-American native tribes. The war was unpopular in New England (with its pro-British sentiments), and the Americans made a failed attempt to invade Canada. Victory at the Battle of Lake Eerie was countered by defeats in the east and the burning of Washington, D.C. The Treaty of Ghent in 1814 led to the conclusion of the war, but news was not received until after the Battle of New Orleans, in which American honor was restored. Around 15,000 died throughout the conflict.

The final American conflict during the ‘long’ eighteenth century was the War of 1812 (1812-1815), sometimes viewed as part of the Napoleonic Wars. The British impressed American sailors into the Royal Navy and continued to support anti-American native tribes. The war was unpopular in New England (with its pro-British sentiments), and the Americans made a failed attempt to invade Canada. Victory at the Battle of Lake Eerie was countered by defeats in the east and the burning of Washington, D.C. The Treaty of Ghent in 1814 led to the conclusion of the war, but news was not received until after the Battle of New Orleans, in which American honor was restored. Around 15,000 died throughout the conflict.