Responding to COVID in NYC

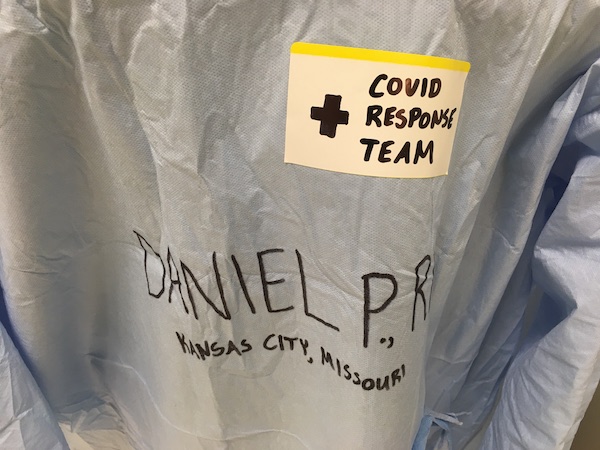

At the beginning of April, I travelled to New York City to assist a critically understaffed hospital in the coronavirus pandemic. It was an experience unlike any that I have ever had.

Part of what made the experience so unbelievable was the uncanny sense of feeling like I was ‘going off to war.’ Gradually, over several days, I came to the decision that I would travel to New York City, after I heard NY Governor Cuomo’s appeal for help. The evening before I signed up, I sat outside, listening to the birds singing. There was a profound peace and calm all around. Yet I knew that I would be traveling over a thousand miles, to enter a place of complete chaos. And so it happened.

On Sunday morning, April 5th – less than 48 hours after signing up – I flew from Kansas City to LaGuardia International Airport. The plane carried only about 9 passengers – and 8 of them were nurses. Both airports were deserted. As the airplane descended out of the clouds, I had a sweeping view of the Manhattan skyscrapers – including the recently-arrived USNS Comfort.

Getting an Uber, I travelled to my hotel, the staging place for hundreds of nurses. Because so many nurses were coming to help – and because of bureaucratic red tape – it took a few days to actually be assigned to a location. During this time I was constantly on call – ready to be called up at any moment for duty. I spent much of this time studying up on the care of patients with COVID, including how to best care for patients on ventilators.

Eventually my assignment arrived – the emergency room in an inner-city hospital. It is hard to describe all the feelings and emotions – but I remember the first time that we arrived at the hospital. Everyone was on edge – what was going to happen? One of our agency administrators got on the bus to ‘wish us well’ and tell us that we were going off to fight a battle. As the massive tour bus pulled up to the hospital, we all got out and entered the front lobby. There was immediate chaos – people yelling at us – ‘social distance!’ ‘keep moving!’ ‘follow the arrows!’ ‘don’t stand so close together!’ At the same time, people swarmed in and out in various colors of scrubs. We processed through checkpoints – getting our temperatures taken, given a mask if we weren’t wearing one – and then, eventually, led on a long, winding route to an orientation area.

When my shift in the ER started, it was further chaos. We were led in a group and then placed individually with our nurse preceptors. None of us knew the layout of the department. I had never worked with that charting system, nor did I know where anything was. And of course, everyone was covered in personal protective equipment. Between my scrub top, long-sleeved T-shirt, surgical gown, another protective gown, a surgical cap, a mask, and a face shield, I was sweltering within minutes.

As the nights passed, I quickly learned how to operate in this new environment. COVID patients came in every night, some of them in critical condition. One man was so oxygen-starved that it took four people to restrain him, just to keep him from tearing his oxygen off in a fit of delirium. Codes were called on the overhead paging system all night long. Not only that, but I ended up working in the ICU several nights, managing multiple patients on ventilators. While this may not have been ideal, I was working with some amazing coworkers – and we had a phenomenal sense of teamwork and camaraderie, where everyone helped everyone.

Sadly, many patients who came to the hospital never made it out. But what about COVID is so dangerous? While it isn’t fully understood why, coronavirus causes a dangerous type of viral pneumonia that often progresses to a uniquely dangerous syndrome called ARDS – Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. If the lungs are like thousands of tiny balloons, it takes energy to inflate those balloons, with every breath. Accumulating fluid outside the balloons means that you have to work harder to inflate the balloons, since the fluid is pushing against the balloons. As the lungs continue to fill up with fluid, it becomes harder and harder to inflate the balloons, and the ability of the lungs to absorb air diminishes.

For patients with ARDS, ventilators take over the work of breathing, by filling the lungs with air. Like an exhausted swimmer, the body will eventually give up in trying to inflate the lungs against pressure. At that point, just like an exhausted swimmer will drown, so the exhausted body will run out of oxygen. But if you throw the swimmer a life raft, the raft will keep him afloat. Similarly, a ventilator will do the work of breathing, so that the body can rest. In theory it is life-saving – but many COVID patients continue to go downhill, even with the support of a ventilator.

Originally, I intended to be in New York City for three weeks – but it ended up being seven weeks. The Emergency Room where I worked was critically understaffed, and they desperately needed traveling nurses to assist. In a record that I hope to never beat, I worked 46 night shifts in the space of 48 days – not including the days that I was on call, awaiting an assignment.

The days blended together. I began to forget what day of the week it was. Although every day brought unique situations, there were only two main tasks every day: work and sleep. Eventually, as the crisis began to subside, I began to think about going home. One foggy and overcast morning, I got off shift for the final time – ready to begin the journey home.

Read more from Baptist Press.

Wow. What a journey.

Thanks for serving