The Eighteenth Century: The Great Events

The eighteenth century may seem distant, but it looms large in its influence, even today. Last week we surveyed the great tides and movements that swept the century, tugging relentlessly at the people, organizations, and power structures of that era. Today we turn to the great events that dramatically affected the flow of history.

This is part of a series on the eighteenth century. You can also view the Tides of History, Great Britain, and America.

The Glorious Revolution (1688)

Starting off the ‘long’ eighteenth century is the Glorious Revolution in England, a near-bloodless overthrow of the Stuart dynasty and King James II of England. The Stuart dynasty was harshly intolerant toward the Puritans, but lax toward Roman Catholicism, even as they held control of the Anglican church. As the English monarchy moved toward closer ties with France and Catholicism, members of Parliament became increasingly concerned about the changing balance of power.

William III, Prince of Orange, was – in essence – the head of the Dutch Republic. He was also wary of the changing balance of power toward Catholicism, and he was easily persuaded by the Parliamentarians to intervene. (The “balance of power” was a very important concern to Europeans; wars were sometimes fought for no reason at all except to prevent a change in the “balance of power”). William sailed to England, James fled with hardly a shot fired, and Parliament chose William and Mary as the new monarchs.

William III, Prince of Orange, was – in essence – the head of the Dutch Republic. He was also wary of the changing balance of power toward Catholicism, and he was easily persuaded by the Parliamentarians to intervene. (The “balance of power” was a very important concern to Europeans; wars were sometimes fought for no reason at all except to prevent a change in the “balance of power”). William sailed to England, James fled with hardly a shot fired, and Parliament chose William and Mary as the new monarchs.

Under William and Mary, the rights of Roman Catholics in England were limited, but Protestants outside the Anglican Church began to see increasing freedom. The Bill of Rights of 1689 limited the power of the monarchy and gave more power to the people. It was the beginning of an age of relative toleration and liberty. Yet it did not create a more pious society. Britain veered toward Deism until the Great Awakening.

War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714)

At the beginning of the Eighteenth Century, the map of Europe looked somewhat different than it does today. The Empire of Spain held vast overseas possessions in both North and South America. France also held large sections of North America. Germany did not exist, but in its place was the Holy Roman Empire, which was neither Holy, Roman,  nor an Empire. Rather, it was a conglomeration of both large and small principalities – most notable of which was Austria. Great Britain and the Dutch Republic were both powerful nations, intent on claiming control of the seas. Great Britain held large sections of North America, while the Dutch held the valuable East Indies (modern Indonesia).

nor an Empire. Rather, it was a conglomeration of both large and small principalities – most notable of which was Austria. Great Britain and the Dutch Republic were both powerful nations, intent on claiming control of the seas. Great Britain held large sections of North America, while the Dutch held the valuable East Indies (modern Indonesia).

In 1700, Charles II of Spain died. This left two options: the Spanish Empire would go to France, or it would go to the Austrians. Either option could upset the balance of power. Charles willed the Spanish Empire to Philip, the grandson of the French king, but other nations were not pleased. The ‘Grand Alliance’ – containing Britain, the Dutch, and the Holy Roman Empire – opposed this. The Grand Alliance was afraid of France and Spain being united into the same power bloc.

The war went in favor of the Grand Alliance, but events suddenly took an unexpected course. The Grand Alliance supported Charles, the Archduke of Austria. When his brother Joseph died, Charles became emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. Suddenly the Dutch and British didn’t want him to also become the king of Spain – too much power! They decided to end the war. At the Treaty of Utrecht and several other treaties, the Spanish king Philip agreed to renounce his eligibility for the French throne, in exchange for recognition by the Grand Alliance. Various territories were swapped, and the British came out ahead of the Dutch.

Between 200,000-400,000 died during this war – a war to preserve the balance of power. This included over a thousand in North America – all to ensure that one man didn’t get too much control.

War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748)

Plenty of other wars plagued Europe after that of the Spanish Succession, but the next significant one for the entire continent was the War of the Austrian Succession. Again, a king died, and there was considerable controversy over who would take his position. Could Maria Theresa, Archduchess of Austria, inherit the dominions of her father, including the Kingdom of Hungary? Britain, the Dutch, and parts of the Holy Roman Empire said yes. France, Prussia, and the Spanish said no.

Plenty of other wars plagued Europe after that of the Spanish Succession, but the next significant one for the entire continent was the War of the Austrian Succession. Again, a king died, and there was considerable controversy over who would take his position. Could Maria Theresa, Archduchess of Austria, inherit the dominions of her father, including the Kingdom of Hungary? Britain, the Dutch, and parts of the Holy Roman Empire said yes. France, Prussia, and the Spanish said no.

The fight was on, all over the world. In North America, this took the form of King George’s War and the War of Jenkin’s Ear (yes, a war that was literally named after a man’s ear). In India, this took the form of the First Carnatic War. In Europe, the war consisted of many conflicts around the continent. But more was at stake than just Maria Theresa. It was a perfect opportunity for monarchies to fight their traditional enemies and gain further power. France and Spain recognized this as an opportunity to reclaim territory from the Holy Roman Empire. Britain found this to be an excellent chance to wear away the power of the French.

In the end, around 300,000-400,000 lost their lives in another attempt to gain power and maintain the “balance of power.” Once again, peoples in distant places found themselves at war simply because their imperial government had a squabble about inheritance laws. These colonies were also exchanged like gambling chips at the treaty tables.

The Seven Year’s War (1756-1763)

In 1754, the young George Washington attacked a tiny force of French Canadians with his own tiny force of Virginian soldier. Little did he know that his attack was the tiny spark that would ignite the bloodiest war of the century. The Seven Year’s War spanned not only North America and Europe, but territories on five of the seven continents, including the West Indies, India, the Philippines, West Africa, and South America. In other words, this was a true ‘World War.’ Over the course of the conflict, between 800,000 – 1,300,000 people died. The Napoleonic Wars were bloodier, but they happened outside the ‘true’ eighteenth century, at the end of the ‘long’ eighteenth century.

Of course, like so many other wars, the latent hostilities that fanned the flames of war were present long before Washington’s force attacked. Every European power had its special reasons for fighting, and they usually centered on the desire for more power, or to maintain the balance of power.

Of course, like so many other wars, the latent hostilities that fanned the flames of war were present long before Washington’s force attacked. Every European power had its special reasons for fighting, and they usually centered on the desire for more power, or to maintain the balance of power.

Washington’s assault was the first spark, but his fight occurred several years before the Seven Year’s War technically started. The main cause of the war was the territory of Silesia. During the previous major war (the War of the Austrian Succession), the Prussians had taken Silesia from Austria. Now Austria wanted it back.

France and Austria, even though they were traditional enemies, decided to ally against Prussia. Britain feared a change in the balance of power, and she supported Prussia. Every other major European power was soon involved on one side of the conflict or the other. In the end, the British had come out clearly ahead of the French. The Prussians maintained control of Silesia, and the French and Austrians were clearly defeated.

The American Revolution (1775-1783)

Across the sea, colonists of British America were increasingly frustrated. They felt as if they were treated as ‘second class citizens,’ and they had no representation in Parliament. Further taxes, which they could not vote against, did not help their feelings. But ‘taxation without representation’ was by no means the only source of frustration.

During the War of the Austrian Succession, colonists had joined together to capture the French Canadian city of Louisbourg; Americans were displeased when, at the treaty table, the British simply handed it back to the French. While Americans were spared most of the hardships of massive continental wars, they were still able to view these conflicts from afar, and every battle with France on the continent led to Native American incursions on the American frontier. French Canada, significantly less populated than British America, relied heavily on Native American allies. The Native habit of collecting scalps tended not to improve relationships with indigenous peoples, especially since there was already conflict over land ownership.

During the War of the Austrian Succession, colonists had joined together to capture the French Canadian city of Louisbourg; Americans were displeased when, at the treaty table, the British simply handed it back to the French. While Americans were spared most of the hardships of massive continental wars, they were still able to view these conflicts from afar, and every battle with France on the continent led to Native American incursions on the American frontier. French Canada, significantly less populated than British America, relied heavily on Native American allies. The Native habit of collecting scalps tended not to improve relationships with indigenous peoples, especially since there was already conflict over land ownership.

When Britain restricted immigration west of the Appalachian mountains, colonists felt frustrated again. Then, in 1774, Parliament (which now controlled the Province of Quebec) passed laws that removed references to Protestantism in the oath of allegiance in that province. This was seen as an effort to establish Catholicism as a state religion in British territory, and it further worried the colonists.

The American Revolution was truly revolutionary, for it aimed to throw off the British monarch and establish a government of the people. It was based on Enlightenment ideals, and it drew from the idea that America was to be a special nation, a kind of ‘light to the nations’ which – from the bloodsoaked plains of Europe – would be seen as a haven of peace, prosperity, and piety. Thomas Jefferson summed it up best when he said, “Peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations…entangling alliances with none.”

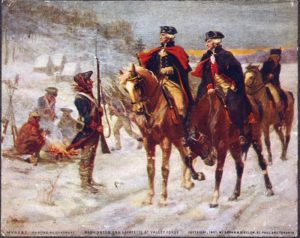

At first, the Americans seemed doomed to fail, especially after defeats in the New England colonies and a disastrous attempt to invade British Canada. When Washington launched a daring raid on a snowy Christmas Eve, the advantage began to turn, and it was further helped when the British launched their failed invasion from Canada. In the southern states, a guerilla war pushed the British back. Finally, seeing the success of the Americans, the French decided to join as allies. Spain and the Netherlands also declared war, and Britain agreed to peace at the Treaty of Paris.

The war was conducted with perhaps 100,000 – 150,000 deaths total. In comparison to recent wars it had been relatively small, but its influence was disproportionately large.

The French Revolution (1789-1799)

The French were on the victorious side of America’s Revolution, but they gained little from the war except significant debt. For over a century, France had been highly taxed as its aristocracy squandered their wealth in ostentation and empire building. There was a deep and bitter divide between the upper and lower classes. The situation had been significantly worsened in the previous century when harsh measures came down on the Huguenots. These French Protestants were a significant proportion of the middle class, and when they fled the country, they represented a tremendous loss of economic talent.

By 1789, the king, Louis XVI, faced a serious debt problem. He was advised to call a session of the Estates-General, a representation of the nobles, clergy, and commoners, to address the problem. Such occurrences, in the past, had often resulted in new taxes, but this time, the kettle was about to blow. The Third Estate, the section of representation that stood for the people, moved to take control. Voting to call themselves the ‘National Assembly,’ they swore to given France a Constitution. The king tried in vain to end their sessions, but they refused.

By 1789, the king, Louis XVI, faced a serious debt problem. He was advised to call a session of the Estates-General, a representation of the nobles, clergy, and commoners, to address the problem. Such occurrences, in the past, had often resulted in new taxes, but this time, the kettle was about to blow. The Third Estate, the section of representation that stood for the people, moved to take control. Voting to call themselves the ‘National Assembly,’ they swore to given France a Constitution. The king tried in vain to end their sessions, but they refused.

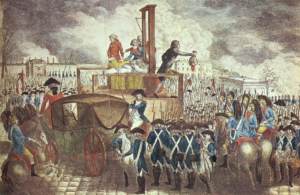

Then, on July 14, 1789, insurgents stormed the Bastille as a symbol of French despotism. As the situation become more radical, the king and his family was forced to move to Paris. Eventually he decided to flee secretly, but he was found and brought back to the capital. The situation spiraled out of control in the bloody September massacres of 1792, as mobs of citizens murdered and plundered openly. Louis XVI was finally executed at the guillotine on January 21, 1793 – the guillotine being the most famous symbol of the revolution. Because it was (assumed to be) instantaneous, it was viewed as a ‘democratic’ capital punishment, suitable for any individual, aristocrat or commoner.

A “Committee of Public Safety” gained authority and soon instituted a reign of terror. Citizens were executed on baseless charges and chaos and terror reigned. Marat and Robespierre are the most infamous names associated with this reign and – like Stalin two centuries later – they routinely wrote down names of potential ‘criminals,’ who were immediately rounded up and executed. Eventually, both men were murdered and a “Directory” took control of the nation. Further, the revolution was extremely anti-clerical and anti-monarchical. Priests were slaughtered in their churches, noblemen were tortured, and priceless buildings of the state and church were destroyed in violent rampages. The Committee aimed to create a state in which reason was worshiped, and the Christian calendar of seven days in a week was unsuccessfully changed to a ten-day week. Dates were no longer calculated from the life of Christ, but from the beginning of the Revolution.

The period of the Revolution was marked by nearly continuous wars, as well as civil war. Other nations were terrified of the revolutionary spirit spilling into their lands, but they were unable to prevent the French from repeated victories. During this period, the death toll in France was 40,000 to 250,000. In the Revolutionary wars, there were an additional 250,000-1,000,000.

In the end, the French Revolution was undoubtedly the most significant event of the eighteenth century; it was also perhaps the second most significant event of the second millennium, after the Reformation. It was the ‘coming of age’ of secular humanism, and in many ways it was an exact portrait of the story that would be played out in countless dictatorships of the twentieth century. The French Revolution was world Revolution. As G. V. Prinsterer says, “The Revolution is a unique event. It is a revolution of beliefs; it is the emergence of a new sect, of a new religion; of a religion which is nothing but irreligion itself, atheism, the hatred of Christianity raised into a system.” “I take the Revolution in its world-historical idea. It did not exist in its complete form before 1789. But since then it became a world-power and the battle for or against it fills history.”

The Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815)

France was in political chaos, and everyone knew it. But no one was strong enough to single-handedly change the situation, except one man. Napoleon Bonaparte had successfully commanded French troops during the revolutionary wars, and he staged a coup to take authority. He then faced off against a series of five coalitions of European allies. These allies were primarily headed by Great Britain.

Napoleon was a brilliant strategist, and one of his greatest victories occurred against allied Austrian and Russian forces at the Battle of Austerlitz. On land he was virtually invincible, but on the sea, his navy was decisively defeated at the Battle of Trafalgar. It had previously suffered a stunning defeat by the British Royal Navy at the Battle of the Nile, during the Revolutionary Wars.

Napoleon was a brilliant strategist, and one of his greatest victories occurred against allied Austrian and Russian forces at the Battle of Austerlitz. On land he was virtually invincible, but on the sea, his navy was decisively defeated at the Battle of Trafalgar. It had previously suffered a stunning defeat by the British Royal Navy at the Battle of the Nile, during the Revolutionary Wars.

France invaded Spain and Portugal, and the British fought a prolonged war there. Napoleon’s downfall began with a disastrous assault on Russia, which turned into a nightmare. Eventually he was defeated at Leipzig and his enemies exiled him to Elba. The Continental powers, terrified for so long by the dangerous ideas of the French Revolution and Napoleon’s stunning strategies, reinstated the Bourbon Dynasty on the French throne.

But Napoleon was not finished. In a stunning move, he escaped his exile, travelled back to Paris, and recruited another army. He intended to reestablish his empire. The panicked European powers hastily reassembled their armies and met him at the Battle of Waterloo, where Napoleon was defeated again. This time he was exiled to the remote island of St. Helena.

At the Congress of Vienna and the Treaty of Paris, the European powers reestablished the French monarchy and redrew the borders of Europe. It was a significant war, involved some 3.7 million deaths. Napoleon was considered the antichrist by some. The memory of the war would last for generations, and it laid the hostilities that would finally erupt in World War One.

Conclusion

The eighteenth century was a century of contrasts – refined aristocratic fashion and brutal slavery and revolution. It was marked by violent wars, and Americans rightly thought of continental Europe as a perpetual bloodbath. On the other hand, the death tallies of the eighteenth century are minimal compared to those of the twentieth century: more died in the First World War than in all the major wars of eighteenth-century Europe combined. The point of this survey, however, is not only to focus on the grim statistics. It is also to paint the picture of life in the eighteenth century. These events were the backdrop to everything else that happened during this era.

This is part of a series on the eighteenth century. You can also view the Tides of History, Great Britain, and America.

Daniel,

Daniel,

Once again, an excellent post. Great summary of the Wars of the eighteenth century!

I think it’s also a good reminder that ideas have consequences. Certainly there were many ideas behind these events, including the divine right of kings, Enlightenment Ideals, the worship of man, and man’s God-given rights.

As you allude to, it’s important to understand these events because they laid the groundwork for important events and wars to follow.

In your estimation, which event do you think was the most foundational or monumental and why?

Hi Joshua,

Thanks for your comment. Yes, these events were certainly the results of ideas.

I would definitely say that the French Revolution was, far and away, the most significant of these events. It was the flowering of secular humanism, of life lived apart from God. It brought with it all the consequences, for better or worse, that come along with that idea. It was Marxism and Leninism before their time. It was a revolt from the way that the world functioned, on a much deeper and more profound level than anything that the American Revolution brought.

Daniel

Wow, thanks for being so much time and effort into this article! I’ve heard of most of these wars, but never all together spanning the century like this. I wish we would learn from history! It seems to be the downfall of every nation, we somehow believe that we are more invincible than our forefathers, that we are more smart: and that the mistakes that happened in the past will never happen to us. What do you think it will take for us as a nation to change in following Gods ways and ideas versus those ways and ideas that were birthed during the French Revolution??

Hi Elizabeth! Glad to hear from you. I know, it was eye-opening for me to do the research into these wars and rebellions. Like you say, we somehow think that we are invincible, even though every error of the past keeps returning in the present.

As far as how we would change to follow God’s ways…well, that is partly a matter of God’s Spirit being at work in the world. For our own meager part, it involves living out our faith in such a way that the world recognizes that something is different, and being drawn to that difference. But in the end, it is ultimately about what God determines to do. He may or may not change the direction of America. But he does call us to faithfulness. Unfortunately, we are currently heading in the direction that was marked out by the French Revolution…

hi, I just want to ask for your summary about this how did these shape our society today?

Great question. One massive impact of these events was to create within America a distaste for the foreigns imperial wars of Europe, which dramatically shaped how the United States was eventually created. Americans believed that they had a unique position, on the far side of the Atlantic, so that they could avoid the entangling wars of empires. I discuss this a little on the section about the American Revolution. The American Revolution also was an impetus for the French Revolution, and today, the world has mostly adopted American-style representative democracy (even if it is often mixed with corruption in many parts of the world). The French Revolution also laid the foundations for the so-called ‘secular’ state (truly a misnomer, since the ‘secular’ state is in fact an anti-religious state) – a tradition that continued through the thinking of Karl Marx and the USSR, and is today the domain of the leftist/progressive movement. In all of these ways, the 18th century has had an outsized influence on the present.