How to Read Sacred Literature: Six Principles

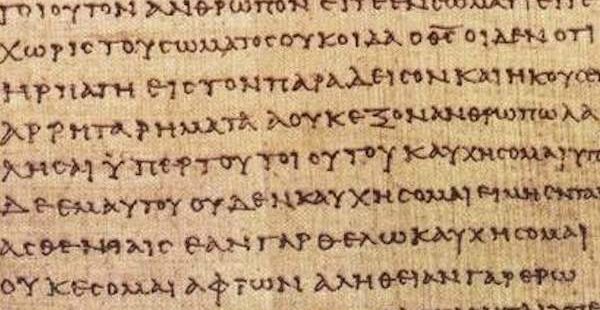

If you lived one thousand years ago in medieval Europe, your experience of reading would be very different. Most likely, you couldn’t read – only one woman out of every hundred, and five or ten men out of every hundred, knew how to read. Even if you had the knowledge, there wasn’t much to read: prior to the invention of the Gutenberg press in 1440, the number of books in the entire continent could be numbered only in the thousands, meaning that you might have access to a Bible and a few other volumes, if you were lucky. Because books were so valuable, only the best books were copied (by hand!), and it was assumed that you would read, reread, and read again those volumes that you had access to.

All of that has changed today. You can find hundreds of books, selling for 50 cents a piece, at the local thrift store. Somewhere between 600,000 to 1,000,000 books are published every year. There are books about every conceivable subject, and with so many options, it’s impossible to begin to read even a tiny fraction of the books available. (I once calculated that if I read a book a week for the rest of my life – and assuming that I live to 80 – I will still only read about 2500 – only 0.002 percent of the world’s nearly 130 million books.)

What this means is that we read most books quickly, skimming for information. Other times, we read books in order to enjoy a new story, one which we have probably not heard before. There is little reason to reread a book. But this is surely not how sacred literature (such as the Bible) is to be read. How should we read such literature? How do we learn to read sacred literature in the way that the medievals, or the ancients, read such writings?

The Principle of the Sacred

Sacred literature is not just different, it is sacred. That means that there is something special about it, something that is ‘set apart’ about it. It belongs on a different level. It is connected, in some way, to the spiritual realm and to God. This means that, if you are going to read it well, you need to read it differently than how you read other books.

The Principle of the Sacred asks you to realize that reading, itself, is a religious act. You are initiating an encounter with the Divine – an opportunity to learn from, and be shaped by, divine thoughts. Not everyone will approach sacred literature with faith, but that is the ideal. Rather than reading like a skeptic, approach sacred literature like a disciple: you are willing to forego judgment and suspend skepticism. You want to see if there is deeper truth, more profound meaning, that you have never before encountered.

It’s often to helpful to take a moment to pray before picking up the Bible. It’s the mental equivalent of ‘taking off your sandals’ (as the ancients did) before coming intothe presence of God. It signals to yourself that you are entering holy territory, and it’s an opportunity to ask God to enlighten you with his truth.

The Principle of Reflection

Sacred literature embeds deep meaning. It isn’t meant to be rushed through. It deserves deep reflection, and the more time that you invest in it, the more that you will profit from it.

Consider, for example, the first words of the Gospel of John: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made. In him was life, and the life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.”

These five verses proclaim deep truth. They call us to think deeply about them. What is ‘the Word’? What is the relationship between ‘the Word’ and ‘God’? In what sense could this ‘Word’ be in the beginning? How can it create, and how does it have life? In what way is this life ‘the light of men’? And what is the meaning of this conflict between light and darkness? All of these questions come to mind in these five verses.

While we should ponder these questions, we can often find the answers as we continue to read. Keep reading the text, but keep important questions in mind. Reflect on the meaning of the various stories and sayings that the text presents. You might want to grab a cup of coffee, sit in a comfortable chair, and linger over the text as you reflect on it and ask questions.

The Principle of Detail

Every word in sacred literature exists for a purpose. There are no ‘extra’ words in the text. That is why you should try to understand why specific words and phrases and even stories are included in the Bible. How do they push the narrative forward? What do they tell us about God, ourselves, and the universe?

Don’t be content to skip over words and ideas that you don’t understand. You might leave them behind for a time, in order to see if there are further clues throughout the rest of the book, but don’t assume that they are ‘unnecessary.’ Similarly, if you find yourself unsure about something because the text doesn’t tell you, no need to worry. It clearly isn’t necessary for you to know in order to get the point! Every detail, and lack thereof, is important.

The Principle of Relationship

Because sacred literature is God’s communication with humanity, it reveals a lot about him. It tells us, directly, what is pleasing to him and what is displeasing; it also tells us, indirectly, what he values and what is unimportant to him. The Bible communicates God’s plan for the world, it tells us his priorities, and it helps us learn what he is up to.

This is what you learn when you are in a relationship with someone. You begin to learn about how they operate, on a deeper level. You recognize what they value, and you learn what motivates their actions on a deeper level. Approach the Bible with a desire to learn these things about God. In the process, you build a deeper relationship with him.

The Principle of Response

Pay attention to how you feel as you read sacred literature. The Bible evokes emotions, and those emotions are designed to help us process truth. You might feel anger, joy, shame, astonishment, or hope as you read the Bible. These emotions come as we get to know who God is, and they are a very important part of developing relationship with him. If you are reading the Bible well, you should feel fear when contemplating his wrath, anger when considering the things that he hates, joy when anticipating his plans for the world, shame when recognizing how you have betrayed him, astonishment as you learn about his mighty works, and hope as you see what he has done for you. Such emotions are signs that you are reading the Bible well. God is becoming real to you – he is not just a storybook character.

The Principle of Submission

The purpose of learning about the divine is not so that you can keep leading your life with increased spirituality. It is, instead, to conform your terrestrial ways to spiritual truth. This means that you come with submission, a willingness to mold your life, habits, and thoughts to what is ultimately real.

The Bible provides ample opportunity for you to do this. It issues commands, assuming that you will actually obey what is commanded. It reasons with you, under the assumption that you will be persuaded by the truth. It offers truth to you, under the assumption that you actually want to recognize and learn the truth. It gives you hope and promises, presupposing that you desire such things.

Conclusion

There are many principles involved in reading sacred literature, and these six are only a start. However, if you take them to heart, reading with the principles of the sacred, reflection, detail, relationship, response, and submission, then you are much more likely to get real value out of your reading. Reading will no longer be an exercise in skimming for infromation: it will instead be a means of communion with God.