A Summary of the Second Punic War

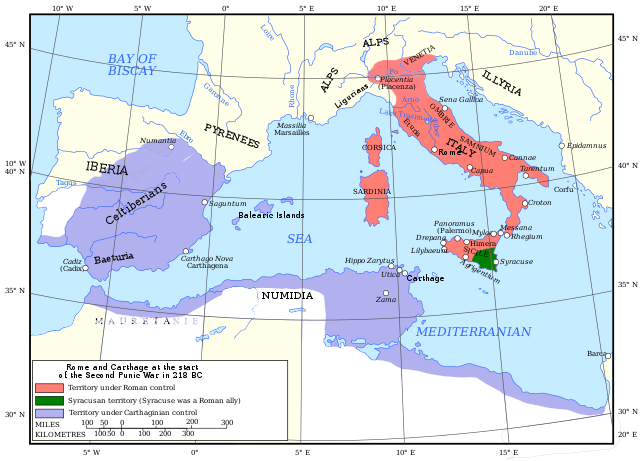

The Second Punic War, which was fought two hundred years before the birth of Christ (in the years 218-201 BC), was the equivalent of the Second World War for the ancient world. It followed the First Punic War (262-241 BC), and these two conflicts pitted the two greatest states of the Mediterranean against each other in a spectacular, bloody, and dramatic showdown.

Prelude

The Roman Republic was steadily growing in power, but had not yet established an empire. It owned the Italian peninsula, and its strength was centered in its capital, Rome.

The city-state of Carthage held vast territory around the Mediterranean. The city itself was located in North Africa, but as it owned a maritime empire, it had many settlements around the Mediterranean.

After losing the First Punic War, Rome imposed a crushing tribute on Carthage. The Carthaginians then had to crush a revolt caused by unpaid mercenaries in the barbarous Mercenary War (241-238 BC). Carthage was exhausted, but she had a fearless leader named Hamilcar Barca. This Hamilcar, a successful general in the First Punic War and the Mercenary War, had a plan for how he would make Rome pay.

Hamilcar took his army to Iberia (modern-day Spain) and conquered new territory. Although it was technically Carthaginian territory, he ruled it like his own kingdom, raising eyebrows among the Romans. But Hamilcar calmed their fears, indicating that he was only conquering Iberia so that he could control the silver mines. With all this wealth, he could pay the Carthaginian debt to the Romans. The Romans let him be.

Hamilcar had three sons. His most famous was Hannibal, whose name means ‘Baal-Be-Gracious-To-Me’ (Carthage was founded by the Biblical city of Tyre, which worshipped the Canaanite god Baal). At the age of nine, his father made him swear an oath of eternal hostility of Rome. Even though they weren’t at war, Hannibal was being prepared for his life’s work.

Eventually, Hamilcar died, leaving his Iberian domain to Hannibal. In 219 BC, Hannibal’s forces conquered the city of Saguntum, infuriating the Romans and starting the Second Punic War.

Hannibal Crosses the Alps

The Romans prepared to invade Carthaginian territory in Spain, and they even wanted to launch an invasion against Carthage itself. But they weren’t prepared for the one thing that Hannibal did: he launched his own invasion against Italy, marching through the Alps and then south into Italy. It was the one way that the Romans never imagined he would attack.

Hannibal’s crossing of the Alps, in the autumn of 218 BC, was incredibly difficult. He lost perhaps two-thirds of his army to the terrain and bitter cold. The native inhabitants of the mountains attacked his force, sometimes rolling boulders onto them, and many of the men and animals in his army fell to their deaths. But, to the astonishment of the Romans, they made it across.

After a small but decisive victory at the battle of Ticinus (218 BC), Hannibal began to gather allies among the inhabitants of northern Italy, swelling his army to 40,000. The Romans, meanwhile, had rushed their army from Sicily. The army commander, Sempronius, was up for elected, and he wanted a big victory. His haste caused the Romans to be ambushed at the Battle of Trebia (218 BC), where thousands (maybe even tens of thousands) or Romans were killed. Hannibal’s army swelled with new allies, to a size of 60,000.

Hannibal then marched across the Appenine Mountains, a range in central Italy, bringing his forces closer to Rome. The Roman army, realizing that Hannibal was now positioned between them and Rome, rushed to catch up – and fell into another trap at the Battle of Lake Transimene (217 BC). Here, Carthaginian soldiers trapped the Romans on a narrow path between a mountain and a lake, then killed or captured 25,000 of the 40,000 Roman soldiers.

Rome was now in an uproar, as Hannibal seemed unstoppable. In response, they elected a ‘dictator.’ This was a specified office in Rome, for emergency situations. A dictator had absolute power for six months, at which time he gave up power. The Romans chose Quintus Fabius Maximus, who had a unique strategy. Recognizing that the Carthaginians won every pitched battle, he refused to attack, and instead kept his armies close to Hannibal, letting his enemy burn, loot, and destroy his way through the Italian countryside.

This ‘Fabian Strategy’ was effective, because it prevented Hannibal from winning pitched battles, and the Carthaginian force was too small to attack Rome directly. But the strategy also infuriated the Romans, who chafed as they watched their countryside destroyed while doing nothing. Hannibal played this well, destroying everything in his path except for the personal estates owned by Fabius. This caused much whispering in Rome, where many people assumed that Fabius had struck a private deal with Hannibal.

At one point, it appeared that Fabius had bottled Hannibal up in a large, fertile valley. The Romans sealed off every escape from the valley, and the Carthaginians had only a matter of time before they would starve. But Hannibal had an idea. He prepared his troops to move, as silently as possible, for a night march. That night, the Roman guard watched as a vast multitude of fiery lights advanced toward one of the passes. The Roman guards rushed toward this multitude, ready to attack and destroy the Carthaginians. But when they finally reached the lights, they were amazed to find, not men holding torches, but oxen with torches tied to their horns. In the chaos, the Romans had left their post to pursue the lights, and the Carthaginians slipped away through one of the now-unguarded passes.

The Battle of Cannae

After Fabius’ term as dictator ended, the Romans selected two consuls to control the army. The two men each commanded the army on alternating days, and Paullus was cautious, but Varro had campaigned for his office on the promise of marching a vast army against the Carthaginians and defeating them. On Varrus’ day, he led the army into battle, against the advice of Paullus. The Roman army had over 86,000 men, while the Carthaginians had only 50,000.

The Battle of Cannae (216 BC) is among the most famous battles in military history, for Hannibla was able to surround and destroy a large army with a small one. He created a long front with his 40,000 infantry, and sent his 10,000 cavalry to destroy the Roman horsemen. He placed his weakest troops in the center of the line, and the Romans, seeing this, decided to drive into the center and exploit their weakness. Normally, the Romans would space their troops out more, but because of the unique way that Hannibal had placed his weakest soldiers in the center, the Romans packed their soldiers into the center of the line in order to more effectively destroy the Carthaginians.

But the Carthaginian center did not break. It slowly backed up, a step at a time, as the Romans fought, but it did not break, and the two sides of the Carthaginian line, which were made of the strongest units, simply held their ground. The result was that the Romans continued to drive in, until they had created a wedge into the middle of the Carthaginian line. At this moment, the Carthaginian horsemen suddenly attacked from behind the Romans, and the two sides of the Carthaginian line began to push the attack and joined up together. The Romans were now completely encircled. Pressed closer and closer together, they were eventually so close that some could not even draw their swords. Then the slaughter began, and by the end of the day, 48,000 Romans were dead and 20,000 captured.

The Roman Delay

After his victory at Cannae, even more of the Italians revolted from Rome and joined Hannibal. But over time, this became a hindrance rather than a help. The Italian allies did not want to join his army and march from place to place, so they did little to actually help his force. But because they were allied to him, they felt that he had a duty to protect them from the Romans, and so Hannibal was forced to constantly march around in order to stop the Romans.

The Romans, however, were in no rush. They had been defeated too many times, so they simply waited. As long as Hannibal did not attack Rome itself, they could continue to wait. And they did so for years.

During this entire time, Hannibal received only one shipment of new soldiers and elephants, sent to a port city in 215 BC. Otherwise, he was entirely reliant on those who had crossed the Alps with him, and on those that he could recruit from among the Italians. This was because of the powerful enemies that he had in Carthage, who resented his abilities. Yet by failing to support him, they were failing to support their best chance of victory.

Later, several armies attempted to join Hannibal. In 207, Hannibal’s brother Hasdrubal Barca crossed the Alps – this time without the same difficulties, since the tribes were friendly. He intended to join his army with his brothers – but the Romans defeated him before the armies joined, and he was killed.

Hannibal’s other brother, Mago Barca, landed an army in northern Italy and stayed there for a couple years, but the Romans kept him from ever being able to join his army with his brothers. Eventually he was called back to Carthage, but died of his wounds on the return trip.

War in North Africa

Finally, in 204 – a full 14 years after crossing the Alps, Carthage sent a message to Hannibal: he was desperately needed back at home. The Romans had launched an invasion of north Africa, and they were defeating Carthage. Despite all of his effort, Hannibal was forced to board ships, with his sailors, and leave Italy.

Meanwhile, the war had gone badly for the Carthaginians in other areas. They lost Iberia, and they lost Sicily, including the famous city of Syracuse. Then, a Roman army landed in Africa, and the Numidians, who had been their allies, changed sides. Two large Carthaginian armies were defeated. It was at this point that Carthage recalled Hannibal back to Africa.

When Hannibal returned to Africa, he was given command of the Carthaginian forces, which faced Scipio, the Roman commander, near Zama. Here, at the Battle of Zama (202 BC),the Romans had the advantage of cavalry, while the Carthaginians had the advantage in infantry. Hannibal’s plan was wise: his war elephants would charge forward, then his troops would mop up the scattered Romans. But Hannibal had met his match in Scipio. The Romans moved out of the elephants’ paths, then formed up again into their traditional formations, and the Carthaginians were routed. Nearly 40,000 Carthaginians were killed or captured. In the end, it was Hannibal’s last battle. The Carthaginians knew they were defeated, and they accepted a Roman treaty. Among other stipulations, they were prohibited from ever again making war without Roman approval.

Aftermath

After the defeat of Zama, Hannibal was chosen for high office in Carthage. He quickly became unpopular, though, when he introduced laws to limit corruption among the governing elites, and finally he was forced to leave Carthage.

Hannibal himself fled to the east. He spent time in various eastern kingdoms, as a sort of advisor for those who were making war with Rome. But he was not very successful in helping his royal patrons to succeed against Rome. Several times he was forced to flee, as the Romans made it a point to demand him as a prisoner from the kings that he helped. Finally, in the year 181 BC – 21 years after the Battle of Zama – on the verge of being captured, Hannibal took poison. In his final words he wrote, “Let us relieve the Romans from the anxiety they have so long experienced, since they think it tries their patience too much to wait for an old man’s death”

As we consider this man Hannibal, one man summarized him well: “He had indeed bitter enemies, and his life was one continuous struggle against destiny. For steadfastness of purpose, for organizing capacity and a mastery of military science he has perhaps never had an equal.” (Caspari)