The Throne of David: Tracing the Gospel in the Book of the Kings

The history of Israel, recorded in First and Second Kings, is like a huge painting, filled with details. Like any good painting, it has a subject, something that our eyes are meant to be drawn to. That subject is the gospel. But too often, when we approach these books, we focus our eyes on the extraneous details: the wars and battles, the kings, the miracles, or the chronology. Too often, we are squinting so hard at the details that we fail to make out the real subject, the gospel.

Even though we often approach these books as a mere historical record, they function as a very incomplete record. They are far from being ‘balanced history.’ You will notice that a lot of attention is paid to some people, while very little attention is paid to others. Further, these books cover 400 years of history – equal to America’s history from the time of the pilgrims to the present. And they do all of that in less than 50,000 words – far shorter than even the most introductory American history. Clearly, the author isn’t trying to give us a general history of Israel. He has more specific objectives: he highlights certain events because he wants to show that Israel’s history has a purpose, a flow, that points to certain truths.

As we see to understand First and Second Kings, we need to consider five different sections of the storyline: the Covenant with David, the United Kingdom, the Northern Kingdom, the Southern Kingdom, and the Destruction and Exile. Each of these segments of the history adds to the narrative, helping us to trace the gospel clearly.

The Davidic Covenant (2 Samuel 7)

When you think of 1 & 2 Kings, you probably think of two books. But originally, they were one book. That’s why I’ll refer to both of them simply as the Book of the Kings.

The first two words of the book, found in 1 Kings 1:1, are וְהַמֶּלֶךְ-דָּוִד. Translated, this says, “And king David.” Even though they are normally translated “Now King David,” it is still clear that they are carrying on a previous thought. These words pick up in the middle of a story. Isn’t that an odd way to start a book, with the word ‘And’ or ‘Then’? Clearly, then, the Book of the Kings is not meant to be a stand-alone volume. It is carrying on a story. And that story is what is recorded in 1 & 2 Samuel: the story of David.

In particular, the story of David contains the record of God’s covenant with David, found in 2 Samuel 7. In summary, David realizes, ‘Here I am, sitting in my beautiful palace, but God is still living in a tent!’ He sends for the prophet Nathan and says, “I want to build a house for God.” Nathan says, “that’s a wonderful idea, why not you do that!” But that very night, God wakes Nathan up and sends him with a message to David: “David, are you going to build a house for me? I’ve lived in a tent for all these years and never was angry about that. In fact, even though you want to build a house for me, I’m going to do something for you. I’m going to build a house for you! So don’t worry about building a house for me – your descendant will do that – because I’ve decided to build a house for you!”

Now, there is a play on words in the Hebrew. We think of a house as a physical building – and the word has that meaning. But it can also have the idea of a dynasty, the people in the house. So David wants to build a house for God – a temple – but God says, I’m going to build your house. I’m going to give you descendants. I’m going to make you into a dynasty of kings:

“(11b) Moreover, the LORD declares to you that the LORD will make you a house. (12) When your days are fulfilled and you lie down with your fathers, I will raise up your offspring after you, who shall come from your body, and I will establish his kingdom. (13) He shall build a house for my name, and I will establish the throne of his kingdom forever. (14) I will be to him a father, and he shall be to me a son. When he commits iniquity, I will discipline him with the rod of men, with the stripes of the sons of men, (15) but my steadfast love will not depart from him, as I took it from Saul, whom I put away from before you. (16) And your house and your kingdom shall be made sure forever before me. Your throne shall be established forever.’” (2 Samuel 7:11b-16)

Now, I’ve said that this is a covenant, but the word ‘covenant’ is not found in this passage. However, there are other passages of Scripture that clearly mark this as a covenant (2 Samuel 23:5, Psalm 89, Psalm 132:11-12, and 2 Chronicles 13:5). And a covenant is, to put it very simply, an agreement to formalize a relationship. God and David were on good terms before, but now they are in a formal, ‘covenantal’ relationship.

It is important to recognize that a covenant is different from a contract. Nowadays we are more familiar with contracts than with covenants. Contracts are oriented around things – like ‘pay $10,000 by July 1.’ But a covenant is oriented around people – like in a marriage, where two people formalize their relationship by becoming husband and wife.

One of the biggest differences between a contract and a covenant is what is expected. A contract demands performance: if you have a contract with someone, the most important thing is that you fulfill your side of the contract. This means that (in our example), you have to pay the $10,000 to the other party by the assigned date. You may not like the other person – you may even hate their guts – but as long as you perform your part of the contract, paying the money within the assigned time, no one can accuse you of ‘breaking the contract.’

A covenant, however, is different. A covenant demands loyalty. In order to keep the covenant, you have to be loyal to the other person. For example, in the covenant of marriage, the emphasis is not on performance. It is not enough to fulfill a certain set of duties so that you can check a box and say, ‘Okay, I’ve done it!’ Instead, the emphasis is on loyalty: being devoted to the other person, not getting involved with other people, but remaining committed to your spouse. That is what a covenant demands.

The ancient Hebrews had two specific words to refer to this concept of loyalty and faithfulness. The first word, chesed, is often translated ‘loyal love’ or ‘steadfast love.’ The second word, ‘emet, is often translated as ‘faithfulness.’ And this is what you look for in a person who is involved in a covenant. Do they demonstrate loyal love to the other person in the covenant? Are they faithful to the relationship, or do they abandon the relationship? As you read the Book of the Kings, look out for these words. Every time that you see them, they imply the idea of a covenant.

You can see one of these words, chesed, or ‘loyal love, in this passage, in verse 15. God guarantees, absolutely, that he will not remove his loyal love from David’s descendants. God is saying, ‘You can be absolutely sure of it, I will be faithful! I will be loyal in this covenant, this formalized relationship!’ And how long will that last? God promises to David, “Your throne shall be established forever” (v. 19). God is promising that David will have an eternal dynasty. This is significant, because God is making a massive promise. The question that we naturally have is, can God keep a promise that big? Is he going to demonstrate that much loyal love and faithfulness to the covenant? To a large extent, that is the question that the Book of the Kings is answering.

There is another phrase here that also deserves attention, v. 14 – “I will be to him a father, and he shall be to me a son.” What does that mean?

In this part of the ancient world, a king was often considered to be the son of a deity. The Egyptians believed that Pharaoh was the son of a god. This meant that he represented the deity for the people – he functioned as a divine representative. The Pharaoh must carry out justice among the people on the god’s behalf. He must wage war and defend the people on the god’s behalf. Hence, to be the ‘son of a god’ meant to represent the character of that deity. By naming David and his descendants as his ‘son,’ God gives them a tall order to fill: they are to represent God’s character to their subjects.

But this works two ways. The king will represent God to the people, but the king will also represent the people to God. What the king does, the people do; he is the nation incarnate; he is the entire nation of Israel embodied and enfleshed in a single man.

Why do I say this? Because when you ask, ‘Who is God’s Son’? The first answer that you get comes from Exodus 4:22-23. God tells us who his son is: “Israel is my firstborn son.” But now we see something more. When we ask the question again – Who is God’s son? – we find a more specific answer: “He [the Davidic descendant] shall be to me a son.” The idea has transferred – or better, it has been refined. Israel is still the son of God, but Israel is now represented by the Davidic king, who embodies the concept of the nation. As I said, the king is the nation incarnate.

This idea is actually common in the ancient world. The king represents the nation. In Genesis 20:4, Abimelech, the king of Gerar, equates himself with the entire nation. We get the same idea in 2 Samuel 24. The entire nation of Israel is punished because David, their representative, has sinned by taking a census.

This idea is called ‘federal headship.’ It is the concept that a single individual represents an entire people. We have something similar to it in the concept of an ambassador. When the ambassador of the United States gives an official message, he is representing us all, and he is speaking on our behalf. Imagine, however, that some country insults our ambassador. They do this, not because they have any personal grudge against him. They do it as a way to insult the nation as a whole, because he represents us.

Of course, I don’t need to mention how significant this idea is later in the Bible. Paul argues this, very famously, in Romans chapter 5, where we see that Adam is the ‘federal head’ of his people, just as Jesus is the ‘federal head’ of his people. In the same way, the Covenant with David is establishing this ‘federal headship,’ where the Davidic descendant is going to represent the people. He is the ‘Son of God’ and his actions have consequences for everyone who is in his kingdom.

An analogy might help us to understand the significance of this covenant. The analogy is that of a living tree, and the light is maintained by the sap that flows through the wood. In this analogy, the entire tree is the Davidic Covenant. The trunk of the tree is the descendant of David, the king. Everyone in the kingdom is attached to the trunk, and so they are the branches of the tree. The sap that flows through the tree and keeps it alive is the ‘loyal love’ and ‘faithfulness’ – the ‘emeth and chesed – of God. How do you get to experience God’s loyal love and faithfulness? Well, you need to be attached to the trunk; you be associated with the covenant.

I would argue that, in order to understand the Book of the Kings, we have to realize the significance of the Davidic Covenant. David isn’t just a historical figure; he is the key to understanding Kings. That is why he is mentioned 96 times in the book of the Kings. David, in fact, is the gold standard for what it means to be a king, since God’s assessment of him is that he “did not turn aside from anything that he commanded him all the days of his life, except in the matter of Uriah the Hittite” (1 Kings 15:5).

The United Kingdom (1 Kings 1-11)

When we enter the Book of the Kings, you can’t imagine a more dramatic scene. David is dying. The question is, who will take his place? David is visible with all his flaws: the effects of his polygamy are present with different sons vying for the kingdom. David himself is a weak and helpless man, lying shivering in bed. His weird relationship with Abishag just highlights how powerless he is. And then Adonijah tries to steal the throne, even though Solomon is God’s hand-picked heir!

We know that Satan was trying to destroy God’s plans all the way from the book of Genesis. Now, here is a very real target for Satan to aim at. If he can somehow ruin the Davidic dynasty – maybe keeping Solomon from the throne, or destroying the descendant of David – then he can thwart God’s designs in the world. It was promised that Satan would try to do this. In Genesis, God said that there would be enmity between the serpent and the seed of the woman. In Exodus, a new Pharoah tried to kill all of the male infants. Balak tried to get a curse over the seed of Jacob. All throughout the Old Testament we find this Satanic scheming. Here it is again. David isn’t even dead, but the demonic plot is advancing: Satan is trying to ruin the Davidic dynasty by having the wrong guy inherit the throne. The question for everyone is, will God keep his covenant to David, maintaining loyal love and faithfulness to David?

God does so – and that is why, in 1 Kings 3:6, after receiving the throne, Solomon can praise God by saying, “You have shown great and steadfast love to your servant David my father…and have given him a son to sit on his throne this day.”

Then Solomon starts a royal purge. It’s time to pull the electric chair out, dust off the cobwebs, and get rid of all the enemies of the state. But there are some people who deserve to die – like Abiathar – who get a pass. Why? Because he shared in all of David’s affliction. Notice that – David is gone, but even after his death, David has a merciful influence. People who are connected to David receive grace that they don’t deserve.

What you have in Solomon’s reign is a taste of what life is like when both God and the Davidic descendant are faithful to the covenant. Solomon’s reign is wildly successful, filled with blessings and grace beyond your craziest imagining. This happens because God is demonstrating faithfulness and loyal love, and Solomon (the Davidic descendant) is obedient. The result is blessings for everyone – life the way that it is supposed to be.

The high point of Solomon’s reign is the dedication of the temple in 1 Kings 8:20. After building the sacred space that David wanted to build, Solomon throws a big party for the whole nation. They eat barbecue and listen to a long speech. The main point of Solomon’s speech is, “The Lord has fulfilled his promise that he made” (1 Kings 8:20). This is the pinnacle, the moment of fulfillment, where God did what he said he was going to do. Now, it appears, everyone gets to enter a golden age – the age of the Davidic Covenant. Surely, the future looks bright.

But there is something more going on in the Temple than just blessing for the people of Israel. The blessing of the Covenant with David extends beyond the Jewish people. Solomon prays for foreigners (8:41-43), recognizing that they will also come to the temple to pray. When they do so, he asks, would God please hear their prayers also? Then, all the peoples of the earth will know God’s name and fear him. The Temple – to put it simply – isn’t just for Jews. It is a house of prayer for all nations. So God’s grace, through the Davidic line, is going to extend to people in the whole world!

Now let’s return to the analogy of the tree. We saw already that in order to receive the loyal love and faithfulness of God – the sap that flows through the tree – you need to be connected to the Son of David, the trunk of the tree. However, do not think that the covenant is a strictly Jewish thing. Remember that a major purpose behind the idea of Israel is that Abraham’s seed would be a blessing to all the families of the earth. We see this idea in the Davidic Covenant as well: the descendant of David is a blessing to all the families of the earth. The sap of God’s loyal love may indeed be flowing only through the tree, but the fragrance of its leaves and flowers is wafted throughout the entire earth.

The stage seems set for a golden age. The Davidic descendant is ruling, obedient to God, and the temple is standing. God’s faithfulness and loyal love are clearly evident. But as we know, this golden age doesn’t continue. Because, even though Solomon is a wise ruler, he still disappoints. He isn’t everything that we want in a ‘Son of David.’ He fails in his role as ‘Son of God’ and as federal head of the Israelite people. For these reasons, God says that he will tear away the kingdom from him.

Yet even in his anger, God still remembers loyal love and faithfulness. This is clear in 1 Kings 11:11-13. David’s influence is again obvious. It is as if God is yelling at Solomon, ‘You sinned! You broke the covenant! You weren’t faithful to me! So I’m going to take the kingdom away from you… but… but… wait a second. David. I remember David. Because of David, I’m going to be gracious. I’m going to delay the judgment. It won’t come in your days, but in the days of your son. And I’m going to ease the judgment. I won’t take away the whole kingdom. I’m only going to take away part of it – because I remember David.’

The Northern Kingdom (1 Kings 12 – 2 Kings 17)

About this time a man by the name of Jeroboam enters the plot. He is a rebel, someone who is working to overthrow Solomon. However, far from receiving condemnation, God actually encourages him in these efforts. God promises to give him ten of the twelve tribes. God also makes an offer to Jeroboam in 1 Kings 11:38: “…if you will listen to all that I command you, and will walk in my ways, and do what is right in my eyes by keeping my statutes and my commandments, as David my servant did, I will be with you and will build you a sure house, as I built for David, and I will give Israel to you.” In effect, God is saying to Jeroboam, ‘I’m going to give you a chance to get in on all the privileges of this covenant with David. If you are obedient, you can have all the same sparkling, shiny things that I gave to David!

When the Israelites separate from Solomon’s kingdom, the language that they use is very direct: “What portion do we have in David? We have no inheritance in the son of Jesse. To your tents, O Israel! Look now to your own house, David.” (1 Kings 12:16). If you think back to the analogy of the tree, remember that the trunk of the tree is the Davidic king. The sap flows through that trunk. When the ten northern tribes leave, these branches are voluntarily cutting themselves off.

Jeroboam, meanwhile, is a very shrewd politician. His kingdom goes to war with Solomon’s son, and so – developing a civic religion that keeps his people patriotic – he fashions two golden calves and puts them on opposite sides of the kingdom. For this sin, he is repeatedly condemned.

It is important to note that in the northern Kingdom of Israel, the kings are never compared to David. Instead, they are compared to Jeroboam. Jeroboam is the negative standard against which the northern kings are compared.The bar is so low, but can any of the kings get above it? The answer is, very few indeed.

Because of this sin, God is clear about the judgment that will come on Jeroboam. He will not inherit the promises of the Davidic Covenant. In 1 Kings 13 we come across a very odd story of a man who arrives to make a prophecy against one of the altars of Jeroboam, in the sanctuary where they are worshipping this calf. The prophet cries out, “O altar, altar, thus says the LORD: ‘Behold, a son shall be born to the house of David, Josiah by name, and he shall sacrifice on you the priests of the high places who make offerings on you, and human bones shall be burned on you” (1 Kings 13:2).

Where is this ‘King Josiah’? Despite a terrifying glimpse of coming judgment, God’s patient character comes on full display. I’ll let Peter Leithart explain. He says, “We turn to 1 Kings 14, expecting a Davidic king named Josiah, but he is nowhere to be found. History continues decade after decade, and still no Josiah. By the time we finally get to Josiah (2 Kings 22-23), our minds are so numbed by the details of the chronicle that we have likely forgotten all about the prophecy of the man of God. Every king but Shallum (15:13-16) continues in the sins of Jeroboam son of Nebat, who caused Israel to sin, and yet no Josiah. If we are reading attentively, each reference to Jeroboam’s calf shrine (and there are over sixty of them) reminds us that Yahweh threatened to destroy Bethel’s sanctuary. And each time, we wonder: How can he let them get away with this? Where is Yahweh? Is there a God who judges in the earth?”

The point here is that God is far from being the vengeful, brimstone-breathing Deity often imagined in the Old Testament. Yes, Josiah will come with judgment. No, he won’t be arriving today. Or tomorrow. Or this year. Or this decade. Or even this century. God is very, very gracious with a rebellious people. So we carry on through the mind-numbing battles, the lists of conquered and conquering kings, the casualties and provinces, the prophecies and the sins, that make up the chapters that come. Years, decades, and centuries of mercy, all because God is warning, pleading, and entreating with the nation to return to him before the judgment is unleashed. But they do not. And so, finally, in 722 BC, the Assyrian empire destroys the northern kingdom.

The Southern Kingdom (1 Kings 12 – 2 Kings 23)

In many ways, the southern Kingdom of Judah deserves the same judgment that the northern kingdom receives. In fact, in some ways, they almost seem worse. They defile the temple. They worship false gods on the temple premise. Often, it is even the Davidic king himself – the representative of God and the federal head of Israel – who leads the nation in these sins.

However, the Southern Kingdom has a ‘get out of jail free’ card that it uses, again and again, to keep from being destroyed, even when it deserves terrible judgment. That ‘get out of jail free’ card is the Davidic Covenant. Because of the Covenant, Judah escapes God’s destruction on multiple occasions. They escape, not because of what they do or how they behave. They escape because they are still connected to the tree, and God remembers David.

There are many examples. In 1 Kings 15:4, despite Abijah’s evil lifestyle, “for David’s sake the LORD his God gave him a lamp in Jerusalem, setting up his son after him, and establishing Jerusalem” (1 Kings 15:4). In 2 Kings 8:19, even though Jehoram sins heinously before God, “Yet the LORD was not willing to destroy Judah, for the sake of David his servant, since he promised to give a lamp to him and to his sons forever.” (2 Kings 8:19).

In the words of Stephen Dempster, “There are twenty northern kings in about 200 years, and twenty-one kings in the south in a period almost twice as long. More importantly, there are ten dynastic changes in the north and none in the south. It is not just that geographical and political factors account for the northern lack of stability…the decisive cause lies elsewhere. By contrasting the south with the north and highlighting the name ‘David’ in the south, the instability of the northern dynasties accentuates the Davidic dynasty and its foundational promise. The name ‘David’ shines in the text as a lamp in the darkness…”

But even for the good kings, God reminds them that the mercy that they receive is because of David and his covenant. When righteous Hezekiah seems fatally ill and the city of Jerusalem in danger of destruction, God makes it clear that the mercy he will receive is because of his connection with David: “I will add fifteen years to your life. I will deliver you and this city out of the hand of the king of Assyria, and I will defend this city for my own sake and for my servant David’s sake.” (2 Kings 20:6).

We saw already that in the northern kingdom, Jeroboam is the negative standard against which all the kings are compared. In the southern kingdom, David is the positive standard of comparison. Again and again, we read that a king did what was right “as David his father had done” (1 Kings 15:11) or that he did not do “as his father David had done” (2 Kings 16:2).

The tension becomes palpable in 2 Kings 11. Athaliah, pagan daughter of Ahab, seizes the throne and unleashes a bloody holocaust on David’s descendants. Like a chainsaw-wielding murderer, she is trying to cut down the entire tree of the covenant. For six years it seems that she has succeeded. The covenant appears to be ruined and God didn’t maintain his faithfulness to David. Then we find that there is still one little boy, Joash. Like Moses of old, he was threatened by a monarch intent on destroying God’s plans. And, like Moses of old, he was rescued by a princess. The tree still stands. Once again, we see what is going on behind the scenes: a cosmic demonic struggle to destroy God’s purpose by destroying the royal seed.

Even as the Kingdom of Judah declines, a remarkable king arises. His name is Josiah. In terms of measuring up to the standard, Josiah is remarkable: the assessment at the beginning of his reign says, “he did what was right in the eyes of the LORD and walked in all the way of David his father, and he did not turn aside to the right or to the left.” (2 Kings 22:2). But amazingly, he receives even higher commendation at the end of his reign: “Before him there was no king like him, who turned to the LORD with all his heart and with all his soul and with all his might, according to all the Law of Moses, nor did any like him arise after him.” (2 Kings 23:25)

Dempster does an excellent job of explaining how Josiah is the pinnacle of the southern kingdom: “A close reading of Kings suggests that a climax is reached with Josiah’s accession to the throne. After all, his birth is announced 300 years in advance and he is regarded as the restorer of true worship (1 Kings 13:2). When he does arrive, he reforms and reorganizes a corrupt and apostate Judah on the basis of an old Torah scroll discovered in the temple. He purges the land of idolatry. The description of his reign merits almost two entire chapters (2 Kings 22-23). His kingship is presented as incomparable. Unlike any other person, including David himself, he serves God with ‘all his heart, soul and capacity’ (2 Kings 23:25). This was urged of Israel, but sadly no Israelite ever measured up to this standard. Josiah may have represented a messianic hope in a way that previous Davidic kings did not. In other words there seems to be an air of excitement and anticipation with Josiah’s coming, Might he be ‘the one who is to come’?”

What comes of Josiah? Does he usher in the golden age? Does he fulfill all the hopes for the Davidic dynasty? No. In fact, he is something of a flop when it comes to being a general. The author of the Kings says that when he went up to battle against the Egyptian Pharaoh, “Pharaoh Neco killed him at Megiddo, as soon as he saw him.” (2 Kings 23:29). So much for the hopes of the golden age. So much for Josiah being the ultimate descendant of David. We must look elsewhere.

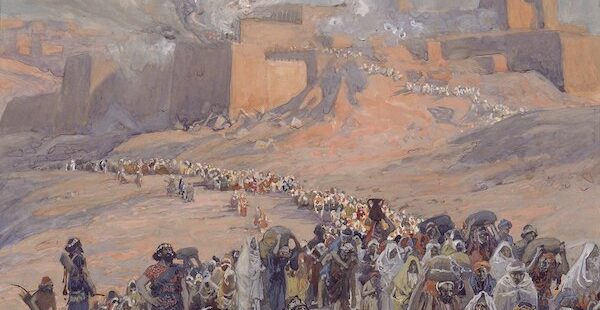

Destruction and Exile (2 Kings 24-25)

By the time that Judah is destroyed, in 586 BC by the forces of Babylon, the southern kingdom has a full criminal record. The nation has strayed from God, filled the land with innocent blood, perverted justice, and set up graven images. What is amazing is not that God finally gets around to justice; it is that God took so ridiculously long to do so. As Leithart says, “If anything, the God of 1-2 Kings is irresponsibly indulgent toward his people, a God who does not seem to realize he cannot run the world without a dose of law and order. By the time Judah is sent into Babylonian exile in 2 Kings 25…we are saying, “It’s about time! What took him so long?” God has gone above and beyond in showing leniency and loyal love to David’s descendants.

But when Babylon comes, we are suddenly left with a gaping void. What becomes of the covenant? God was faithful to David’s house all the way from the beginning of the book, where Solomon took his place, through the dangerous struggles of wars and empires. The dynasty survived Athaliah and her murderous rage. Clearly, God’s providence protected the House of David! But now what? Now there is no more Davidic dynasty. The tree has been cut down. Nothing but a stump remains.

Or is there more? Even as the Jewish exiles toil under the Babylonian sun, and the smoke has long since cleared from the rubble of the Jerusalem temple, the author of Kings notices something small but significant. Jehoiachin, exiled king of Judah, finds favor in the eyes of Evil-Merodach, King of Babylon. He is freed from prison. Kind words are spoken to him. And he is given a place at the Babylonian table. It seems so small – so insignificant – but it is a reason for hope. There is still a Davidic descendant. The dynasty is not quite extinguished.

Concluding Thoughts

Three implications stand out.

First, this overview of the Book of the Kings shows us a unique way to read the Bible. We often read it simply to find help for our daily lives. Yet the Book of the Kings rarely contains helpful sayings to guide us through daily life – it isn’t always directly applicable. For example, reading about how Zimri burnt the king’s palace over him doesn’t give you much help for facing the day’s challenges. But sometimes we should avoid the question, “what direct lesson does this have for me today’ (as good a question as this sometimes is). Instead we can ask, ‘What is God doing in history? How is he fulfilling his covenants?’ The answers will yield some unique perspectives.

Second, pay close attention to the idea of David’s descendant being both Son of God and federal head. He represents God to his people, and he represents his people to God. We see both of these aspects in the kings. The king is supposed to demonstrate God’s character, just like David did – he is the Son of God. And he is also the federal head: when David’s descendant does evil, the whole nation is punished; when he obeys, the whole nation is blessed. If you are represented by David’s Son, his obedience or disobedience is – we could say – the most important thing about what God thinks of you, or how God treats you. This, of course, is a theme that has massive implications, not just positionally in theology, but also practically in how you think about the Christian life. Who are you? If you are related to the Davidic descendant, you are justified. This isn’t ultimately about your performance; it has to do with the actions of your Davidic representative. You are a vine connected to the branch.

Third, the Book of the Kings ultimately points us toward the coming Davidic King. Who is he? God hasn’t ended his loyal love and faithfulness. It has been on display time and again. At the same time, we have been disappointed on many occasions by the succession of Davidic descendants described in the book. Not even Solomon or Josiah are perfect! By showing this lineup of failures, the book points us toward the coming Son of David. He will be a perfect representative of God, the ultimate ‘Son of God’ who represents God for us and who represents us to God. In this way, the Book of the Kings directs us to look with great hope and expectation for the coming King, the ‘Son of David.’ When we recognize him, we should cry out, like the blind beggar on the way to Jericho in Mark 10, ‘Son of David, have mercy on me!’

In summary, the Davidic Covenant is absolutely essential for understanding the Book of the Kings. The descendant of David is the Son of God, who represents God to the people. He is also the federal head who represents the people to God. Within this tree, the sap of God’s loyal love and faithfulness flow to all who are connected. Despite the external storms of persecution and the internal rot of apostasy, God has faithfully protected that tree. Now, as the book ends, nothing is left but the stump of a sawed-off tree-trunk. But when we see Jehoiachin lifted up from prison, we once more have hope that Isaiah’s famous prophecy still has the hope of being fulfilled: “There shall come forth a shoot from the stump of Jesse, and a branch from his roots shall bear fruit.” (Isaiah 11:1).

Addendum

I should add, as a side-note, that I’ve been tremendously helped by several authors who have gone before. Dale Ralph Davis has written excellently on these books with his commentaries 1 Kings: The Wisdom and the Folly and 2 Kings: The Power and the Fury. Peter Leithart helpfully discusses the gospel in his Commentary on 1 & 2 Kings. Stephen Dempster traces several significant themes in Dominion and Dynasty: A Theology of the Hebrew Bible. And Gentry and Wellum are the best resource I know of on the Davidic Covenant in Biblical Theology, in Kingdom Through Covenant: A Biblical-Theological Understanding of the Covenants. I’m indebted to these writers for numerous insights.